During a break in a mixing session at a recording studio in Milan, Gomo Tulku, a Tibetan-American hip-hop artist, plays the sample he's inserting into the intro of his debut EP—a group of vocalists singing what sounds eerily like a Tibetan Buddhist chant. One of his Italian producers had it programmed into his keyboard, and when Gomo first heard it, he recalls, he said, "That's dope, I want that. Yo, that's my culture!"

Swiveling in his Aeron chair behind the multitrack console, conferring with the engineers on the mix ("

Si, perfecto, bello"), Gomo Tulku looks every bit the part of an aspiring rapper: jeans, black down vest, gray porkpie hat, oversize black-and-gold Super glasses (a Milan brand favored by Jay-Z and Rihanna). But the 23-year-old is not quite the playa he portrays in the video for his first single, "

Photograph," in which he drinks in a club and rides in a stretch limo while a host of leggy Italian beauties grind on him. Known as the Rapping Lama, Gomo spent his childhood being groomed to be a high-ranking lama, and the video caused a minor uproar in the online Buddhist community. But Gomo is nearly a teetotaler and insists "Photograph" is a wholesome breakup song about the one romance he's had since leaving the monastery. "Listen to the lyrics!" he says. The hip-hop eye candy was his Italian director's idea.

The tulku in Gomo's name refers to his status—according to Tibetan tradition, a tulku is the reincarnation of a recently deceased high lama, "recognized" as a young boy through a mystical process of omens and visions. Gomo was anointed by the Dalai Lama himself, whose own recognition story is so well known in the West—a peasant boy from the sticks is magically able to identify his predecessor's favorite possessions—it became the basis for a 2002 M&M's commercial.

Gomo has titled his EP Take One because "this is like my first take, my first actual experience in life as a layperson in this materialistic world," he says. Gomo, an ethnic Tibetan born in Quebec and raised in Canada, Utah, and India, is savvy enough to appreciate that his years as a shaved-headed monk make for an irresistible backstory for an MC. His digital loop—hypnotic, rumbling oms that sound like a cross between a bullfrog and a low-pitched Jew's harp—conjures up a world of burgundy-and-saffron-robed monks wielding bone horns. But it also begs the question: When the Dalai Lama, who's 77, leaves the stage, will that world—1,500 years of religious traditions and spiritual explorations—be reduced to an ersatz sample in a hip-hop song?

To an extraordinary degree, America has been colonized by Tibetan Buddhism. At the core of the community are maybe 100,000 die-hard practitioners around the country. Beyond that is a larger circle of several million spiritual travelers who may pick up the Dalai Lama's best sellers or attend his talks. (He's achieved rock-star status, having drawn a crowd of 65,000 to New York's Central Park just to hear him speak.) Helping fuel the phenomenon is the soft (but real) power that makes it a cause c?l?bre and a second religion to the self-help set: the Hollywood stars like Richard Gere in the Dalai Lama's American entourage, the late Beastie Boy (and practicing Tibetan Buddhist)

Adam Yauch's star-studded concerts for Tibet, not to mention the Buddha statuettes,

thangka paintings, and prayer flags that adorn corner yoga studios and health clubs across the country.

For the hundreds of Tibetan tulkus who came of age after the Chinese takeover of their homeland in 1959, India may be where they serve in the monastery, but the West is where the students, the press, and the money are. Yet it's unclear whether the tulku system—which, since its origins in medieval times, has been more about the transfer of monastic power than the recognition of spiritual genius—can continue to advance the Dalai Lama's engagement with the West. The young Karmapa, the heir apparent to the Dalai Lama's mantle as the global face of Tibetan Buddhism, languishes in northern India because of political tensions involving China. In his absence, the young, Westernized tulkus may be the key to turning a new generation of Americans on to Tibetan Buddhism. The problem is, these cosmopolitan tulkus, skeptical of the notion that they're deceased lamas, aren't sure they want the job.

• • • GOMO TULKU: A RAPPER'S SUTRA

Gomo's fate was seemingly sealed at the age of 3, when the Dalai Lama divined that he was the reincarnation of the boy's grandfather, a prominent Tibetan lama. When the official letter of recognition arrived from the office of His Holiness, Gomo's religious mother was "kind of sad, kind of happy," he says. She was losing her son to the monastery but, according to Tibetan Buddhist lore, also being reunited with her father's spirit. Gomo's early life was peripatetic: Born and raised in French-speaking Montreal, at age 5 he moved with his mother (his parents had divorced) to Bountiful, Utah, a mostly Mormon suburb of Salt Lake City. When he was 6, mother and (only) child traveled to the tiny Tuscan village of Pomaia. The next year, the Dalai Lama cut Gomo's hair, the first stage of his initiation into monkhood. "I remember I was nervous," Gomo says. "His presence was really strong." At his "enthronement," Gomo sat on a high, brocaded throne as hundreds of monks and Western students crowded in for a closer look at the new boy lama. "I was like, 'Wow, this is pretty amazing,'" he recalls. "There were photographers from dozens of newspapers and news agencies around the world." He drifts into hip-hop lingo. "The cops, the 5-0, were there, pushing them back."

After a full day in the studio, Gomo and I make the four-hour drive south to Pomaia, arriving at midnight. There, housed in a 19th-century stone villa, is the Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa. "The Little Tibet of Tuscany" (as a tourism website describes it) is a regular stopover for eminences like Richard Gere and the Dalai Lama. Stereotypical Bella Toscana imagery—skinny, conical cypress trees, herb-scented scrubby-pretty landscape—blends well with more recent additions like prayer flags and a giant copper prayer wheel. In the morning, amid the meditation hall's golden statues of the Buddha, ornate silk tapestries, and portraits of the Dalai Lama, Gomo brings a hushed purposefulness to his prayers.

"This takes me back in time to the monastery," he says after finishing his prostrations. "We used to always pray. As soon as I get into one of these places, I try to always have the right thoughts, right intentions, try to remind myself of the purposes that I should be going after." Gomo spent only a year in Pomaia before he was sent to the Sere Je monastery in Mysore, India, to which he would give, all told, 12 years of his young life. His days as a monk went like this: up at 6 a.m., prayers, chanting, memorizing page after page of scripture, and practicing Buddhist logical debate until around midnight each night. "I had a hard time," he says, "not from what I was given, but more from what was taken from me." It doesn't take a Dylanologist to decipher the lyrics to his song "Lost and Found": "All is gone, all is gone, I miss my mama's kiss/ Tryna make a child grown/ By leaving him all alone/ Destined to be on a throne/…Why didn't you, why didn't you stay?"

Gomo remained a good monastic soldier until he was 15, when he seized on a bold idea: to reunite with his mother for a year of American high school. In Bountiful, he was the weird Asian kid who spoke patchwork English and "probably looked like a dumbass." He was still keeping his monk's vows—no sex, no alcohol—a fact he hid from his classmates, except for his best friend. "I wanted to be able to experience that actual kid life," he says. "If they'd known I was a lama, it would've been a disaster." But compared with his previous existence, this sojourn was sheer liberation. His under-the-Bodhi-tree moment of enlightenment took place when he walked into a new Apple store in Salt Lake City and saw the T.I. video "

Bring Em Out" playing on a just-released 60-gig iPod. That in-your-face slice of gangster rap "overwhelmed" him, he says. "The energy it had, it kinda brought me out."

NAMASTÉ AGAIN:

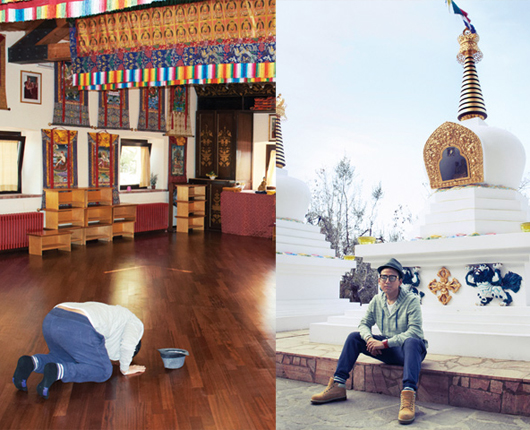

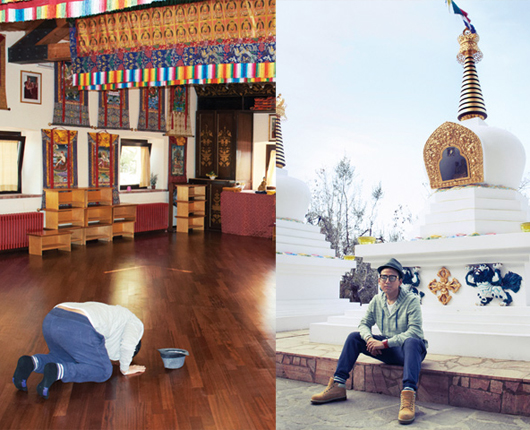

Despite trading the monastery for the recording studio, Gomo Tulku hasn't abandoned Tibetan Buddhism. Left:

He prays in the meditation room of the Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa in Pomaia, Italy. Right:

He pays tribute at one of the Istituto's reliquaries, or stupas.

OM BOY:

Gomo in Milan, where he lives and records. Although he had a strong suspicion that he wasn't going to stay in monk's robes, Gomo returned to Sere Je to gut out the last three years, earning the equivalent of his monastic B.A., because he wanted to finish what he had begun—or had been begun for him. Music, mostly hip-hop, was his lifeline, in the form of headphones and a portable CD player. "I would spend hours just listening to music until, like, five in the morning," he says. "I felt connected to it, like my best friend, the thing that understood me. My attendant would knock on the door and be like, 'Yo, rinpoche, go to bed now.'"

Three years ago, he handed over his robes and moved back to Pomaia. His main monastic teacher was understanding, and he says even his disappointed mother told him, "'As long you don't say the F-word in your song, I'm good.'" For the past year and a half he's been living in Milan, and with the exception of a brief romance with a Guatemalan exchange student, he's been pursuing his music career with monkish devotion, living on a stipend provided by Italian patrons.

Despite being anointed Best Male Singer at last year's Tibetan Music Awards on the strength of one online single ("Photograph"), Gomo can fairly be described as a small fish in a small pond. He is waiting, anxiously, for the music business to lift him from obscurity. In the Milan studio, he listens to playback after playback of "Let Me Down," in which he raps: "Can't choke, I'm feeling like the necktie/ Of the exec who tells you whether your best try/ Will be enough…Afraid of looking foolish, but I'm brave enough to do it/ If you ever doubted your dreams/ Just play this shit and loop it."

He writes tightly constructed, melodic tunes, part rapped, part sung, delivered in a light, sweet voice—think Chris Brown or Drake with a hefty dose of boy band. The Italian arm of Universal Records likes what it's heard, but he's still waiting for a record deal. So far, the elder lamas have remained silent about his career move. I ask Gomo what he imagines the Dalai Lama makes of it. "He's checking out my videos on YouTube—like, 'That's hot!'" Gomo jokes. Then, in the earnest vein that's never far below his hip-hop veneer: "I'd be honored if he knew something about me. I was thinking to actually go see him. Let's see what will happen with the music, and if things start to ripen, maybe I'll go explain it to him."

• • • ASHOKA MUKPO: BUDDHISM'S WHITE SHADOW

When your father is a New York Jew, your mother is an English aristocrat, and your name is Ashoka Mukpo, you spend a lot of time answering questions about your identity. "It's like within 20 seconds of meeting somebody, I've gotta put my whole life on the table," Ashoka, 31, says. "I usually just say, 'Oh, my parents were hippies.' If it's a more formal situation, I'll say, 'Oh, my stepfather was Tibetan.'" And if he's talking to someone who knows something about the story of Tibetan Buddhism coming to the West, he'll share the truth. "Then I say, 'My dad is Chögyam Trungpa,' and God only knows what kind of absurd conversation is going to follow."

Ashoka's mother, Diana, married Trungpa at 16, taking his Tibetan family name, Mukpo. She stood by him throughout the seventies as he built a hippied-out empire centered in Boulder, Colorado, and achieved wider cultural renown as a guru to Allen Ginsberg and Joni Mitchell. Unlike the Dalai Lama, who sticks to the Buddhist basics—minimizing suffering in life—Trungpa initiated his students into the Tantric side of the tradition: the effort to liberate the energies of everyday life to speed up the path to enlightenment. His community, eventually called

Shambhala, was notorious for its booze-and-sex-fueled blowouts that were rationalized as Tantric exercises—transmuting the poison of alcohol or liberating oneself from the attachment of conventional romantic love. "I don't know, man," Ashoka says. "I think if it were this day and age and I rolled up and saw a bunch of white people and all the crazy shit that was going on, I might head for the hills."

By 1980 Trungpa had grown increasingly erratic, and Diana, while remaining devoted, took a lover, Mitchell Levy, Trungpa's personal physician. Trungpa's own sexual infidelity was never at issue—he had been shamelessly promiscuous since puberty. When Ashoka was born in 1981, all eyes in the delivery room were trained on his lily-white skin. Trungpa, true to his credo of "crazy wisdom," was unperturbed. "I was his son," Ashoka says. "It didn't matter that I wasn't his seed—I was his son."

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER:

Ashoka Mukpo (right

) was born to an American Jewish father and an aristocratic British mother but was raised as the son of Chögyam Trungpa, the legendary Tibetan lama who preached enlightenment and practiced free love and alcoholic excess. Left:

Trungpa with Ashoka's half-brother, Gesar, in the 1970s.Ashoka was recognized as a tulku at 8 months old. The previous Karmapa called Trungpa to announce he'd had a dream that Ashoka was the ninth reincarnation of Khamnyon Rinpoche. "They called him 'the Mad Yogi of Kham,'" Ashoka says of his spiritual forebear. "He had a bit of a reputation as a wild man, which I don't think I'm living up to."

Ashoka, who lives in London with his girlfriend, is in New York City for a United Nations conference. Wearing a gray pinstripe suit instead of his usual jeans and T-shirt, he bears a passing resemblance to a young Jeremy Piven. He's smart and tightly wound, guided by a righteous idealism that led him to work for the nonprofit Human Rights Watch for three years after college and most recently to the London School of Economics, where he earned his master's in international development. In the fall he's off to join a nonprofit working on land rights in Liberia. "It's actually mellower than people think," he says.

After Trungpa's death in 1987 at the age of 48, from the alcoholism that accompanied his relentlessly swinging lifestyle, Levy and Diana married and moved Ashoka to Providence, where family life settled into a closer approximation of the American norm. But Ashoka always knew he'd been marked for a special destiny as a spiritual leader, which was exciting, like having a secret superpower, but which also made him feel like a freak. He recalls the time his parents suggested he take two Tibetan monks who were visiting from a monastery in India to basketball practice. "I told them, 'You guys don't get how incompatible this is with my self-conception right now,'" Ashoka says. "When you're 15, you can't say, 'Dude, I'm a reincarnated spiritual master from the hills of Tibet, and my father was this womanizing, drinking, Tibetan-crazy-wisdom genius' without people thinking you're weird as fuck. Now it's just a pain in the ass."

Ashoka's identity confusion took on a poignant edge during a family trip to Tibet when he was 22. "My title and role is really meaningful to people," he says. "I had old ladies and kids coming up to me and crying. Peasants with nothing offering their life savings. For God's sake, someone put a sick baby in front of my face and asked me to blow on it. I did. I'm not going to be the guy who says, 'This whole thing doesn't make sense for me, sorry!' Sometimes I do feel like it wasn't my decision to take this title on, but now I feel like someone put me in the position of abandoning it."

Ashoka is on his way to a celebration commemorating the 25th anniversary of Trungpa's death at the Shambhala Meditation Center in Manhattan's Chelsea neighborhood—one of some 165 centers that, along with dozens of still briskly selling books, maintain Trungpa's legacy. We arrive late to the burgundy-and-saffron-draped hall crowded with New Yorkers in their twenties and thirties. After an hour or so of sitting on the floor cushions, meditating and chanting, volunteers pass around plates of potluck dinner and cups of sake, Trungpa's favored drink.

Ashoka does his part, eating and drinking merrily. But venturing beyond these rituals to live and teach as a tulku lama won't happen in this lifetime. "For me, going too far down the rabbit hole of Tibetan culture doesn't make any sense," he says. Not that he's discerned any pressure from the Tibetan Buddhist establishment. "It's easy for them to write me off. I'm the white guy."

• • • KALU RINPOCHE: THE PRODIGAL SON

One of Tibetan Buddhism's brightest stars and greatest hopes is 22-year-old Kalu Rinpoche, the head of a global Tibetan Buddhist enterprise of 44 monasteries and teaching centers, including 16 in the United States, that engage thousands of students and disciples. Many of those followers are inherited, the result of his being recognized at the age of 2 as the incarnation of Kalu Rinpoche, who died in 1989 and was one of the most influential lamas in the West aside from the Dalai Lama.

Young Kalu travels the world, mostly alone, visiting his meditation centers and monasteries or just amusing himself in countries with relaxed visa requirements. His real monastery is online—Kalu calls himself "the first Facebook rinpoche," managing a network of personal and public pages with thousands of friends and "likes." Most are generational peers who have discovered that it's pretty cool to get a personal message from a bona fide lama.

Kalu is a lithe, smoothly good-looking young man with a fast-receding hairline, long sideburns, and a white roadster cap—something like a hipster version of a golf caddy. He exudes a pop-star vibe, which is appropriate given his lifestyle. The first thing we establish over the course of a series of Skype sessions is that he's at a hotel in Hong Kong and not, as his Facebook posts lead his "friends" to believe, in India. He likes to play with identity as well. This spring, his personal Facebook page assumed the names of, variously, Kalu Andre (he loves Paris and left there only because his visa ran out), Kalu Skrilles (he's a fan of Skrillex), and George Kalooni (just because).

Born into a well-connected Tibetan family, living in both India and Bhutan, Kalu absorbed Western culture in dribs and drabs as a boy in his home monastery near Darjeeling, India. "We shared—200 people—one small TV," he says. "We watched Van Damme and Arnold Schwarzenegger." He picked up English slang from American films and music (the Backstreet Boys were big). "Since I was a kid," he says, "I don't think, 'This is the West.' I think, 'This is real. This is what I want.'" When he left monastery life two years ago to begin his career as a global emissary, he consumed a decade's worth of popular culture in one giant gulp. Favorites include, in music, Foster the People and deadmau5; on TV,

Gossip Girl ("full of drama"); in film,

The Hangover. "I'm a fan of the first

Hangover—the second was not as good," he says. "I like

Bradley Cooper. He's very attractive-looking."

For all the pleasures of a social-networked life, Kalu is lonely, a Buddhist Little Prince adrift on a cyber-asteroid. "Actually, I never had a true friend," he says. "Never felt that he is or she is my best friend. A relationship is a different thing." About a year ago, he came close to marrying a well-to-do Tibetan girl, and he's currently "on a break" from an Argentine girlfriend. In a later conversation, though, he apologizes for the no-friend remark—"I was a little tipsy and depressed"—and then repeats it almost verbatim but says of the loneliness, "I can handle it."

To appreciate Kalu is to see him as two things simultaneously. He's a troubled kid and a spiritual adept whose gifts were refined during the traditional three-year retreat he undertook in his teens—the last year of which was spent in near-constant meditation and yoga practice. Kalu recognizes that it's time to exert more control over a life that has been marked by emotional chaos. He has shelved a plan to study comparative religion at an American university in order to maintain some measure of authority over his organization. Yet the senior lamas in Kalu's order have had to step in to fill the power vacuum created by his erratic lifestyle and propensity to say whatever is on his mind.

Last September, after a teaching session in Vancouver, someone in the audience asked Kalu about sexual abuse in the monasteries. He replied that he was sensitive to it because he had been molested. That seemed to break through the wall that had sealed his private traumas off from his smiling public persona, which had the aura of an updated, hipper Dalai Lama. Two months later, Kalu returned to his temporary home base in Paris and shot a video that he posted on Facebook. Titled "

Confessions of Kalu Rinpoche," the video has since gone modestly viral on YouTube and turned him into an outcast in the traditional Tibetan Buddhist world and a hero of conscience to some in the West.

In the video, Kalu sits in a hooded parka and tells the camera that as a young teen he was "sexually abused by elder monks," and when he was 18 his tutor in the monastery threatened him at knifepoint. "And it's all about money, power, controlling. . . . And then I became a drug addict because of all this misunderstanding and I went crazy." Near the end of the video, he says in an almost suicidal-sounding whisper: "Anyways, I love you. Please take care, and I am happy with my life."

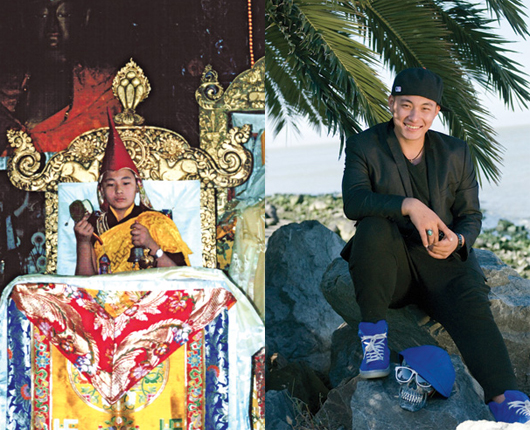

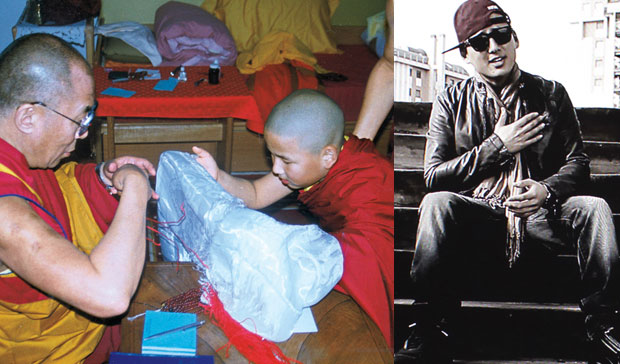

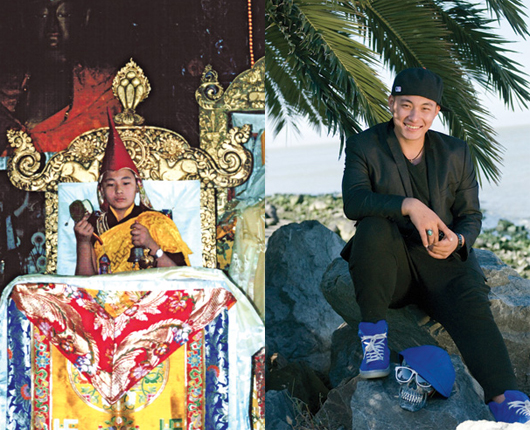

BOYZ II MEN: Left:

At age 2, Kalu Rinpoche was enthroned at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery near Darjeeling, India, where, he says, he was later attacked by a knife-wielding tutor. Right:

Kalu after a public Buddhist teaching event last August in Maui, during his first tour of America.For those who know only the gauzy Hollywood imagery of

Little Buddha and

Kundun and the beatific smile of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, it's almost incomprehensible that Tibetan Buddhism would have its own Catholic Church–style problem. But Kalu says that when he was in his early teens, he was sexually abused by a gang of older monks who would visit his room each week. When I bring up the concept of "inappropriate touching," he laughs edgily. This was hard-core sex, he says, including penetration. "Most of the time, they just came alone," he says. "They just banged the door harder, and I had to open. I knew what was going to happen, and after that you become more used to it." It wasn't until Kalu returned to the monastery after his three-year retreat that he realized how wrong this practice was. By then the cycle had begun again on a younger generation of victims, he says. Kalu's claims of sexual abuse mirror those of Lodoe Senge, an ex-monk and 23-year-old

tulku who now lives in Queens, New York. "When I saw the video," Senge says of Kalu's confessions, "I thought, 'Shit, this guy has the balls to talk about it when I didn't even have the courage to tell my girlfriend.'" Senge was abused, he says, as a 5-year-old by his own tutor, a man in his late twenties, at a monastery in India.

Kalu's run-in with his monastic tutor was anything but typical. According to Kalu, after returning from his retreat, he and the tutor were arguing about Kalu's decision to replace the tutor. The older monk left in a rage and returned with a foot-long knife. Kalu barricaded himself in his new tutor's room, but, he says, the enraged monk broke down the door, screaming, "I don't give a shit about you, your reincarnation. I can kill you right now and we can recognize another boy, another Kalu Rinpoche!" Kalu took refuge in the bathroom, but the tutor broke that door, too. Kalu recalls, "You think, 'Okay, this is the end, this is it.'" Fortunately, other monks heard the commotion and rushed to restrain the tutor. In the aftermath of the attack, Kalu says, his mother and several of his sisters (Kalu's father had died when he was a boy) sided with the tutor, making him so distraught that he fled the monastery and embarked on a six-month drug-and-alcohol-fueled bender in Bangkok, a more extreme Tibetan version of the Amish rum?springa. Afterward, an elder guru persuaded Kalu to continue as a lama away from the monastery and without the robes of a celibate monk, a not-uncommon arrangement. Kalu never said a word to the guru about what had precipitated his flight, a level of decorum that may seem bizarre by Western standards—but Kalu says a form of omertà pervades Tibetan Buddhism.

The Western Buddhist media have barely touched the Kalu story, which may represent its own form of decorum: not wishing to demoralize American converts or roil the waters among powerful Tibetan Buddhists. But some younger, Western Buddhists, like Ashoka and his half-brother Gesar Mukpo, the director of the 2009 documentary

Tulku, say they find Kalu's raw honesty inspiring. Ruben Derksen, a 26-year-old Dutch

tulku who appears in Gesar's film, says that it was about time that Tibetan Buddhist institutions were "demystified and the shroud was removed." Derksen, who as a child spent three years in a monastery in India, wishes to draw attention to the physical beatings that are a regular practice there. "I met Richard Gere and Steven Seagal, and they didn't see any of this," he says. "When celebrities or outsiders are around, you don't beat the kids."

NAMASTÉ AGAIN: Despite trading the monastery for the recording studio, Gomo Tulku hasn't abandoned Tibetan Buddhism. Left: He prays in the meditation room of the Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa in Pomaia, Italy. Right: He pays tribute at one of the Istituto's reliquaries, or stupas.

NAMASTÉ AGAIN: Despite trading the monastery for the recording studio, Gomo Tulku hasn't abandoned Tibetan Buddhism. Left: He prays in the meditation room of the Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa in Pomaia, Italy. Right: He pays tribute at one of the Istituto's reliquaries, or stupas.

BOYZ II MEN: Left: At age 2, Kalu Rinpoche was enthroned at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery near Darjeeling, India, where, he says, he was later attacked by a knife-wielding tutor. Right: Kalu after a public Buddhist teaching event last August in Maui, during his first tour of America.

BOYZ II MEN: Left: At age 2, Kalu Rinpoche was enthroned at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery near Darjeeling, India, where, he says, he was later attacked by a knife-wielding tutor. Right: Kalu after a public Buddhist teaching event last August in Maui, during his first tour of America.